I’m often tagged in tweets or Facebook posts, asking “where do you find digital humanities job postings?”

“Digital humanities” jobs exist in many different forms across different professional fields and disciplines. When seeking a digital humanities job, I recommend that the seeker narrow her focus to the kind of work that she wants to do and in what type of profession.

Below is list of suggested places to find digital humanities jobs. Some of these lists contain digital jobs only, while others require the seeker to browse through more general listings. Remember that not all jobs are posted publicly–DH or others–but are circulated by word-of-mouth. Old fashioned networking is still a good method for finding alt-ac DH jobs.

Please leave comments if I have missed any other good places to find digital humanities job postings, and I will add them to the list.

DH: all fields and professions

- DH Now: http://digitalhumanitiesnow.org/category/news/job/

- UCLA DH Weekly, http://www.cdh.ucla.edu/news-type/jobs/

- HASTAC, https://www.hastac.org/opportunities

Libraries

- DH + Lib: http://acrl.ala.org/dh/category/jobs/

- Code4Lib: http://jobs.code4lib.org/

- Council on Library and Information Resources Post-doctoral Fellows: http://www.clir.org/fellowships/postdoc

Museums

- Museums and the Web: http://museumsandtheweb.com/jobs

- American Association of Museums, Job HQ, http://aam-us-jobs.careerwebsite.com/c/search_results.cfm?site_id=8712

Digital Public History and Humanities (all)

- National Council on Public History: http://ncph.org/cms/careers-training/jobs/

- American Association for State and Local History, http://about.aaslh.org/jobs/

- Federal positions (NPS, Smithsonian, National Archives, et al): https://www.usajobs.gov/

- American Council of Learned Societies Fellows Program: https://www.acls.org/programs/publicfellows/

Faculty, Post-Docs, Admin

- H-net: https://www.h-net.org/jobs/job_browse.php?category_id=29

- American Historical Association: http://careers.historians.org/

- MLA Job List: https://www.mla.org/jil

- College Art Association: http://careercenter.collegeart.org/jobs/

- Chronicle Vitae: https://chroniclevitae.com/job_search/new

- Inside Higher Ed: https://careers.insidehighered.com/

Below are the slides from a talk I was invited to give at Catholic University’s Cultural Heritage Informatics Management Forum on June 5, 2015. I want to thank the forum’s organizers from the CHIM program, Youngok Choi and Ingrid Hsieh-Yee, for inviting me and for organizing this event, which also highlighted some of the great work done by their students and alumni.

Below is the draft of a piece I’m contributing to the 2015 edition of Debates in the Digital Humanities. Yesterday, I co-facilitated a fantastic working group at the National Council on Public History annual meeting with Chris Cantwell, Kyle Roberts, Jason Heppler, Lauren Tilton, and Brent Rogers, where we discussed the differences and intersection of public history and digital history. If you’re interested in looking in on the working group convos, check out our group Tumbler, https://www.tumblr.com/blog/dh-ph. This post comes out my thoughts on what I see as the difference in doing intentionally public digital humanities work.

I’m very interested in hearing your feedback, so please comment and discuss with me.

________________________

Recent calls for finding “public†audiences for scholarly work, engaging “the general public,†and for doing public digital humanities work are encouraging, but only when those calls are informed by the long history of “public†scholarly work with some understanding that the term is contested and changing. We should all acknowledge that is no “general public,†and that we need to get real about audiences.

As a digital public historian, I am attuned to the articles in the Chronicle and conversations–on Twitter, at meetings and conferences–from traditional and alt-academics who invoke “the general public,†when they think humanities professors are failing to be relevant to today’s students and citizens. Some academics respond to critiques of the state of humanities education by showing off digital humanities projects or demonstrate how they are integrating digitally-enabled pedagogy into their classrooms as ways to bridge those gaps between the academy and the public. Additional attention is given to the openness in humanities scholarly processes that capitalize on digital platforms and networks that enable and encourage sharing, remixing, and collaborating are highlighted as the best practices in public humanities. These examples signal positive changes among scholarly communities. But, these changes are drawing on the long tradition of public history work done in and outside of the academy for decades in the US.

On most days, most scholars have no real idea whom they are actually referring to when invoking “the public.†A public approach is challenging to most scholars, because it means identifying and considering audience before beginning a project. This may mean ceding some ground, but when done well, will result in successful public digital humanities projects.

It’s Online, Isn’t it “Public?â€

No.

Research projects, online textbooks, tools, course websites, online journals, or social networks are not inherently “public†digital humanities projects merely because they have a presence on the Web. Launching a project website or engaging in social media networks does not necessarily make a project discoverable, accessible, or relevant to anyone other than its creators. I have given enough panels and workshops on “getting the word out†to know that most academics are clueless in the area. The topic of “outreach†may sound like an afterthought and a one-way marketing blitz, but when done well, it is something that begins with the design of the project. Most important, the “public†should come first.

Doing any type of public-facing digital work requires an intentional decision from the beginning of the project that identifies, invites in, and addresses audience needs in the design, approach, and content long before outreach of a finished project begins. Without doing this kind of audience identification and seeing “the public†as people but an unidentified “other,†scholars may be in danger of blindly attempting to look outside of their own institutions and classrooms and seeing no one.

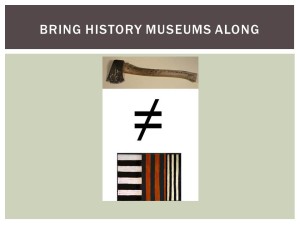

Digital humanities scholars and practitioners have been defined by the digital, which makes the difference in their humanities scholarship. The “public†changes the scholarship in any type of public history and humanities work, and should also in public digital humanities work as well. We should see the practices listed below as related, complimentary, but not necessarily the same.

Public + History = Public History

Digital + History= Digital History

Public History + Digital= Digital Public History

Public + Interdisciplinary Humanities = Public Humanities

Digital + Public Humanities = Digital Public Humanities

Digital + Interdisciplinary Humanities = Digital Humanities

Public + Digital Humanities = Public Digital Humanities

For those interested in pursuing public digital humanities, I encourage you to look to the history of public history and lessons and struggles in that field of practice.

Public History Roots

Public facing and engaging history work outside of the academy and the classroom is a long-standing practice. In the US, public history’s roots can be traced back to the early nineteenth century. White women and men of means volunteered their time to save and preserve community stories, objects, and places. The federal government didn’t get involved in the history business until the late nineteenth, early twentieth century. Federal history and museum programs, such as the National Park Service and Smithsonian Institution, were grounded in practices borrowed and adopted by scientists and naturalists, and used in publicly-funded spaces. [To get a good handle on the history of public history and the historical enterprise, these three books are must-reads: Denise D. Meringolo, Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History (Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2012); Robert B. Townsend, History’s Babel: Scholarship, Professionalization, and the Historical Enterprise in the United States, 1880 – 1940 (University Of Chicago Press, 2013); Cathy Stanton, The Lowell Experiment: Public History in a Postindustrial City (Univ of Massachusetts Press, 2006).]

The public history movement that we know today emerged in universities in the 1970s, responding both to the employment crisis in the US (marketability of history majors) and to the social and labor history movements, engaged communities to question existing social, political, and cultural structures and inequalities. As Denise Meringolo observes, for many self-identified public historians working in universities, and even museums, in the late twentieth century, the “public†was generalized and that unspecified audience was also passive. Public history, offered scholars new ways of communicating (ie, through a museum exhibit), but didn’t necessarily push those scholars to rethink the structures and relationships involved in that communication flow.

Oral historians like Michael Frisch encouraged historians to rethink their roles as facilitators and share authority by interviewing individuals, and listening, and recording those recollections to give individuals a voice in the historical record. As Tom Scheinfeldt has argued, this tradition from the mid-twentieth century forward was “highly technological, archival, public, collaborative, political, and networked,†which represents another branch in the genealogy of digital humanities. Steven Lubar’s oft cited “7 Rules for Public Humanistsâ€

is rooted in and draws very heavily from the public history tradition.

This impetus drove Roy Rosenzweig, a radical labor historian, to found the Center for History and New Media in 1994 with a mission to use digital media to democratize the process of doing history. The work we do at the Center is grounded in a public history methodology that is collaborative and recognizes that “the public†is people.

Who is the “public�

The public is no one if you don’t intentionally identify specific people, groups, communities, and then design a project from the beginning with, for, and about those people. Too often, “the public†becomes the default category of anyone other than ourselves, which can often mean no one. If you have to ask after a project, tool, or program is built, who the audience will be, you built something for yourself. Creating a public digital humanities project must start with “the public,†ie your audiences, users, participants, from the beginning. Public audiences should be imagined as people with interests, lives, agendas, and challenges. To humanize those audiences, the Smithsonian Learning Lab created named personas who represent real teachers, the primary audience for their new digital initiative. Understanding that most historians would not consider audiences from the early stages of digital projects, Dan Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig devoted an entire chapter to audience in Digital History. Sharon Leon will continue to push scholars in this area in forthcoming publication focused on “user-centered digital history.â€

Identifying and collaborating with specific audiences is key to designing and building a successful public digital humanities project that will be relevant, useful, and usable. This means engaging and working with those groups to identify needs, assess functionality, and measure the effectiveness of the project’s platform for communicating ideas at all stages. For Histories of the National Mall, for example, we created paper prototypes for user testing before customizing the Omeka site. We tested content before fully researching and writing the “Explorations,†and we sent graduate students onto the Mall, with friends and family members, to test different iterations of the site, multiple times, before the beta launch. For the original Omeka grant, we surveyed museum professionals before, during, and after the beta release, and conducted focus group testing to gauge needs, assess the effectiveness of the software to meet those needs, and the usability of the administrative interface. These are all important, and time consuming, steps necessary to include in any project’s work plan.

Projects also must be accessible to those identified and potential audiences in a few distinctive ways. First, any public digital humanities project should be designed in ways so that people of all abilities can access it and the content on the web. Second, build in ways that reach your primary users on the platforms they use. This may mean designing mobile first to reach people who access the Web only from a mobile device. If your primary users communicate on one specific social media space, be there. If your uses speak multiple languages, your platform choice must allow for that content to exist and be publishable in those languages.

Third, the language, symbols, and navigational paths embedded in the digital project must be understandable by the primary users and participants. A public digital humanities project should never make the audience feel dumb or uninvited to the party. If we prioritize our needs and assumptions as academics, we are more likely to make that mistake.

Naming is important as well. Name a project something meaningful to your audiences—or intentionally is not associated with a known term. Omeka, for example, fits into the latter category. The Swahili term embodies what the platform is designed to do: display or lay out wares; to speak out; to spread out; to unpack. But the word itself was distinct enough for most users that we could adopt it as the name of a new piece of software. Naming Histories of the National Mall, on the other hand, required that we be direct and tell tourists visiting the National Mall that this site was about the history of that public space. Acronyms and clever naming can work for some public digital humanities project, but you do not want to alienate or mislead your targeted audiences.

Public, First

To do public digital humanities, then, the “public†piece needs to come first. Always.

This process is challenging and often requires a lot of analog work. If you feel that you don’t have the skill set to engage in this type of work, try reaching out and collaborating with a public historian, or perhaps a community activist, to help build your digital humanities project from its early stages. They will share with you lessons they have learned from the field and help you to begin rethinking approaches and methods in new ways. And, you may find you’re building a fabulous new digital thing together that is relevant, useful, and productive for your publics.

(Originally posted to the RRCHNM blog: http://chnm.gmu.edu/news/growing-the-fields/)

Last summer, Sharon Leon and I (Sheila Brennan) led a team at RRCHNM with the challenging goal of increasing capacity within the fields of history and art history for doing digital work. We started with novices and invited them to learn with us for two weeks last summer. At the end, those digital novices transformed into ambassadors who are engaging with the growing community of digital humanities practitioners and who serve as advocates supporting digital history and digital art history work at their institutions and in the fields at large.

The Need

Recent studies conducted by Ithaka S+R document how historians and art historians are reluctant to engage in digital methods and to integrate those methods and related tools into their teaching. The cycle perpetuates itself as these established scholars are then unable to mentor graduate students or even to point them to appropriate training opportunities. These same scholars may also dissuade junior colleagues from pursuing digital work.

Even as digital work is receiving increasing recognition in academic circles, one major question remains for faculty interested in digital humanities and in new publishing mediums: will it count?

Despite decades of amazing work in digital humanities, the skills and methods that are central to pursuing this kind of work have only just begun to penetrate the larger community of historians and art historians. This lack of understanding digital humanities methods and projects then makes it difficult for those scholars to review digital projects, at any stage, for professional journals or for a colleague’s promotion and tenure dossier, never mind advising students interested in pursuing digital work themselves.

Throughout its 20 years, RRCHNM has organized and taught hundreds of workshops on a variety of topics and tools to many different audiences. We have learned that short workshops aren’t enough to transform attitudes and approaches to the scholarly enterprise. For established scholars, who are experts in their fields of study, novices in all things digital, and who may doubt the scholarly rigor involved in digital work, finding training that meets them at their skill level and addresses their disciplinary habits and concerns can be a challenge.

Experimental Summer Institutes

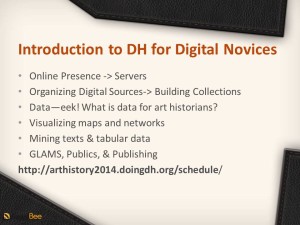

In 2014, Sharon and I organized two summer institutes and crafted curricula to help address these issues. Re-Building the Portfolio ran in July and served 24 art historians, funded by a Getty Foundation grant. Doing Digital History ran in August and served 23 American historians funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities grant.

We framed the daily work by grounding it in the latest digital humanities readings, and then applied what they read in hands-on tutorials that let them test different tools that enabled different kinds of digital humanities work. We offered breadth and also provided each participant with the building blocks for advancing their own digital research projects and developing digitally-inflected pedagogy.

When we started each institute, all 47 of the participants were anxious. Most worried about falling behind on the coursework, getting lost in the daily tutorials, feeling confused, and that they would be the only ones feeling this way. Participants discovered they weren’t alone in their fears and that they had a new community of colleagues with whom they could rely on for support. Each participant established their own domains, installed open-source software, blogged, planned new learning activities for their students, and began rethinking their research projects.

If you’re interested in seeing the daily work, see the schedule or download the curricula for Doing Digital History and ReBuilding the Portfolio.

Measuring Outcomes

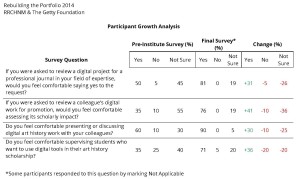

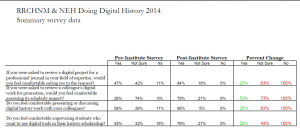

At the beginning of each institute, we did not know how participants would respond to the intensity of the two-week curriculum. We measured progress in two major ways. First, during the institute we surveyed participants a few times to gauge the pacing and instruction, and we adjusted schedules and our approaches accordingly (ie, allowing more time to discuss the readings in the morning sessions). Second, to measure the overall effectiveness of the entire curriculum to change attitudes and practices of the participants, we crafted a pre-institute survey that asked four questions related to our goals and asked the same four questions at the end. In the post-institute survey, we also asked more typical questions following workshops, about overall satisfaction, if participants felt their voices were heard, and if their personal learning needs were addressed.

Questions:

- If you were asked to review a digital project for a professional journal in your field of expertise, would you feel comfortable saying yes to the request?

- If you were asked to review a colleague’s digital work for promotion, would you feel comfortable assessing its scholarly impact?

- Do you feel comfortable presenting or discussing digital history or digital art history work with your colleagues?

- Do you feel comfortable supervising students who want to use digital tools in their history or art history scholarship?

To our delight, 100% of Doing Digital History and ReBuilding the Portfolio participants responded that the institute faculty and facilitators improved their understanding of digital humanities and digital history or digital art history. All participants left as confident digital ambassadors with a todo list, new skills, insights, and motivation to pursue digital work and become active participants in the growing community of digital humanists.

The largest positive growth we saw was in the number of individuals saying that they are comfortable reviewing digital projects for scholarly impact in promotion cases, which we see as a real intervention in effecting change in academic culture and practices.

ReBuilding the Portfolio

The cohort of art historians began their institute more comfortable than the historians discussing digital work with their colleagues and in their ability to review a digital project for a professional journal. The largest area of growth for the art historians was in reviewing for promotion. At the beginning of the institute, only 35% of the cohort felt confident and by the end the total increased to 76%. As a group, the art historians were less confident than their historian colleagues in their ability to supervise or mentor students using digital tools. At the end of the institute, 36% were more comfortable advising, with many more unsure than not.

Doing Digital History

The historians began less confident in their ability to review and discuss digital work than their art historian colleagues. At the start, only 26% responded that they were comfortable assessing digital projects for scholarly content in promotion cases and 74% were not sure. At the end of the institute, the percentages were almost reversed with 79% feeling comfortable reviewing and only 21% remained unsure. We saw a 53% positive growth rate. Across the four categories, we saw a remarkable shift in confidence as not a single historian answered “no†to any of the questions at the end of the institute.

By inviting 47 historians and art historians to engage with digital humanities theory and practice, they were able to better re-examine their own professional assumptions and naturalized processes to see that scholarly production can take many forms. Through analysis of existing projects and through building some things from scratch with their own sources, participants learned how to read, analyze, and interact with digital scholarship.

Looking Ahead

Based the numbers of applicants for both institutes, and separate inquiries, we see there remains a substantial unmet need for beginner DH training that also addresses disciplinary needs. We heard anecdotally from participants that some felt that other outlets for DH training didn’t address their needs as historians and art historians. Even scholars working at institutions with a DH presence found it difficult to get training beyond tools workshops. Also, a few felt like they weren’t prepared to take deep dives into specific digital humanities methods or tools offered by other DH workshops. After taking our summer institutes, however, they felt much more prepared to pursue other types of training.

Commitment

Even with all expenses covered, everyone cannot afford to leave their institutions, families, and lives for two weeks. We have been asked about preparing an institute that is shorter, and even longer. We think that two weeks is the optimal amount of time for an introduction to the broad field of practice that is digital humanities, while diving into disciplinary-specific projects. This time allows for participants to be removed from their existing structures and commitments long enough to immerse themselves, experiment, and see the possibilities for changing their research, teaching, and professional practices.

Running an institute for two weeks also requires a big commitment from the host institution and requires a strong team (ReBuilding Team, DoingDH Team). While Sharon and I led each day, RRCHNM research faculty and visiting instructors helped to shape some individual days of instruction. We also relied on a solid crew of four graduate teaching assistants who led tutorials, provided one-on-one assistance, responded to the backchannel discussions, and updated the institute’s online schedule to reflect any new sites or tools mentioned during the day making the course websites invaluable resources. The logistics of coordinating an institute are not easy and we couldn’t have pulled everything off without the dedication of Jeny Martinez, the RRCHNM office manager. Additionally for each of the two-week institutes, Sharon and I were unavailable for other project work at the Center. Unlike other academic units, the Center operates on a 12-month calendar.

Even with all of these challenges, we enjoyed focusing on one project at a time, teaching as a team, and getting to know our awesome participants.

Some may ask why we aren’t charging for training. We have in the past on a very limited basis. But, we prefer to offer affordable training opportunities that are open to a wide audience, because it aligns with the Center’s mission to democratize history and humanities work. To offer free training, we applied for grants. We have been lucky to receive support from the Getty Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, who are committed to funding training programs for novices in digital humanities.

Future Institutes

This summer, we are developing an institute for art history graduate students, Building a Digital Portfolio, funded by the Getty. We hope to have other opportunities in the future to offer additional institutes for historians and art historians. If we do, we will be sure to announce them on the RRCHNM blog and circulate the news on social media.

I was invited to participate in the “Doing Digital Art History: Reflections on the Field,” panel at the College Art Association conference in New York on February 14, 2015. Below are my slides and my talk.

Unfortunately, I could not give my talk due to a family medical emergency. I was disappointed because I was on the program with some real superstars. Special thanks go to Anne Helmreich of the Getty Foundation who read my presentation on my behalf on very short notice.

Additional thanks go out to the panel organizers: Anne Goodyear, Bowdoin College; Anne L. Helmreich, Getty Foundation; Paul B. Jaskot, DePaul University

At this time last year, we opened applications for Building the Portfolio: DH for Art Historians

Hoping to attract art historians established in their fields but novices in the digital realm.

We had no idea if anyone would apply. Then, we noticed a lot of visits to the application page.

We received 80 applications from art historians hailing from around the world and the US, specializing in different fields, and representing different professional backgrounds in universities, galleries, libraries, and museums.

We had 20 spots. We made room for 24, because we received a few applications from DC- area art historians who didn’t need travel funds. The Getty allowed us to expand the cohort.

We crafted a curriculum to give participants a taste of the different flavors of digital humanities work. We offered breadth, and also provided each participant with the building blocks for advancing their own digital research projects and/or developing digitally-inflected pedagogy.

We discussed theory. They learned new skills. We interrogated DH methods and how they applied to each person’s art history work.

Everyone grew comfortable with sharing what they knew and admitting what they did not, and gained a better understanding of the collaborative nature of DH projects.

Each participant left the institute with their own web domain and a basic knowledge of servers.

They installed open-source software, including WordPress, Omeka, and Zotero; and worked with many others, including Scalar, Voyant , and Palladio.

They all have a better understanding of “data†and why and how art historians might use “data.â€

To measure how well we met our goals, we surveyed participants before they arrived and after the institute ended.

We also took a few short surveys in the middle of the institute to gauge the workload, pacing, and overall satisfaction with the schedule. We tried to adjust accordingly.

We were very pleased with the growth we saw over the course of 2 short—but very intense—weeks.

Most participants left with more confidence in their abilities to review digital work for a professional journal and for promotion review; to advise students in digital art history projects; to discuss, share, and teach topics and approaches in digital humanities generally and digital art history specifically.

At the beginning, for example, only 35% of the participants reported that they felt comfortable reviewing digital work in a colleague’s portfolio for promotion; 10% said no; and 55% weren’t sure.

By the end, 76% said yes, no one said no, and 19% were not sure. We thought that was good progress for 2 weeks of work.

We were most pleased that 100% of the participants were “very satisfied†(the highest available rating) with their institute experiences, with the CHNM team, their new skills, and new abilities to make and interrogate digital art history work.

Thank you to the Getty Foundation for their excitement and support of this growing field. We feel so privileged to have this opportunity to help grow the community of practicing digital humanists.

On Thursday, March 12, 2015, I had the pleasure of speaking at John Nicholas Brown Public Humanities Center with students, faculty, and staff at Brown University. Professor Susan Smulyan also invited me to speak in one of her graduate courses earlier in the day about planning digital public humanities projects. Her students are planning some really neat digital projects. I enjoyed the short time I spent in Providence.

During my talk, took the opportunity to discuss other futures of digital humanities outside of the university.

Here are my slides, and below are my notes per slide. Since the talk was conversational, below are my notes which may not reflect the exact words spoken.

In November, RRCHNM celebrated its 20th anniversary, marking it as the oldest digital history center, and one of the oldest digital humanities centers in the world. Of those speaking, three of the four direct digital humanities centers at universities. The other oversees the Office of Digital Humanities at the NEH and has been tracking the development and recent expansion (explosion) of DH centers on college campuses.

As I sat and listened, I was surprised to hear that no one really talked about the future of centers as existing outside of the university. In fact, some of the futurist possibilities of centers in academic libraries that might allow for speculative computing or play (Nowviskie), are really only possible at well-funded universities—-mine not being one of them. But, I could see that type of process play happening at a museum.

Some of what I did hear resonated: DH Centers benefit from the diversity of skills the concentrate (Ayers); DH Centers are good places for organizing and implementing large-scale projects that cut across disciplines and institutions (Bobley); the academic institutions where centers reside need to commit funding to their long-term stability (Bobley). These seem congruous to how larger museums are staffed, how they collaborate, and how they keep their doors open.

These discussions focused on DH centers in universities, and there are many DH Centers in libraries on college campuses. But, none, as far I know of, in university museums.

No one imagined DH—as a constructed field of practice–centered elsewhere.

What if there were DH centers in museums?

I thought I would take this opportunity to think about the possibilities of DH centers outside of academia. And I’d like to discuss with you all, if this makes sense, if it is practical, or if we all just need to collaborate more.

First, let’s look at DH that is already happening in museums:

I agree with my friend Kimon Keradmidas at the Bard Graduate Center who asserts that DH happens in museums, but just isn’t called that.

“Digital humanities†as I’ve been reminded for years by my colleagues in the museum technology community is a very academic term, and is irrelevant to some, even as it may provide new inroads to scholarly production, discovery of resources, and questions, and opening up some of this work to audiences outside of the academy.

Museums don’t need to get bogged down in definitions that are limiting. Thinking broadly helps to think of multiple roots to DH and to its multiple futures.

I’m not the only one who has been thinking about these communities and bridging and working in ways that enables commons of shared digital resources that benefit many, and driven by museums and dedicated staff.

Neal Stimler of the Met, Mike Edson of the Smithsonian, Mia Ridge of Open University, to name a few. In 2011, Neal Stimler put together a virtual panel of individuals talking about DH in Museums. And there was another panel hosted by CUNY on the Commons, DH in Museums, in Nov 2012.

Mike’s call that museums matter NOW, and that they matter to many publics including scholars, enthusiasts, and visitors of all ages, as museums nurture creativity, civic engagement, knowledge creation. And can do those jobs in better and new ways through digital platforms and methods.

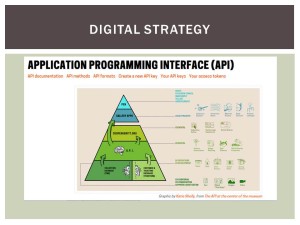

The Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum is one of the best examples of letting Digital Strategies shape their interpretative strategies who also have an amazing lab in the heart of it all.

Cooper-Hewitt is running on an API that drives development of in-person, distance visits, and enables their collection to connect with other digital cultural resources.

When there is an API, with collections data, others can do things with it.

And there is the pen.

Enables physical interaction while at the museum—actual drawing on touch tables. You touch labels, click and save objects from your visit to your own personalized collection page to look at later.

Once collections are available via an API, others can use them and put them into context with other objects:

Rich Barrett-Smith of the Victoria and Albert Museum built Colour Lens—visualizing collection by colors

Makes use of featuring Public Domain images from the Rijksmuseum and the Walters Art Museum, others with permission from the Wolfsonian-FIU, and code from Tate and the Cooper-Hewitt.

Experiments with that data is then shared, on places for sharing open source code, like GitHub.

New modes of Digital publishing, like the Getty Foundation sponsored OSCI Tool Kit, Online Scholarly Catalog Initiative, at art museums.

Scholarly editions, translations of artist works, such as the Van Gogh Letters, Van Gogh Museum was a major partner. Idea to create a new edition, international appeal.

What have you noticed about all of these projects so far?

Art museums

DH Scholars are working with museums, too, such as Ben Schmidt of Northeastern with the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and visualizing 100 years of shipping routes, commodities routes.

Sharing Authority: again the Cooper-Hewitt is asking for input—help us make our data better—not only scholars, but others who might be enthusiasts in a field of expertise.

Curators of American Enterprise exhibit were reaching out, asking for stories that might influence the interpretation and make it into exhibition.

Move toward Openness: Open GLAM, open-source, public domain.

Making museum-quality images available for public uses.

Linked Open Data—connecting collections, persons, places, across institutional repositories.

Example: Smithsonian American Art Museum is leading a group of fourteen institutions from around the country in an effort to build a shared—and searchable—online database of American art, available through Linked Open Data.

Growing number of Maker Spaces in Museums.

That encourage learning, teaching, and tinkering with different varieties of technologies, from sewing to arduinos. Peabody-Essex has a Maker Lounge, and a Maker Lounge Resident focusing on industrial design.

Los Angeles Contemporary Museum of Art has one focusing on art and technology.

It’s a physical space, not unlike some museum education-focused spaces, or maker spaces in libraries. You don’t need a 3D printer to be a maker space.

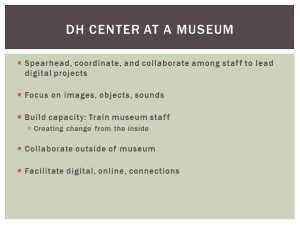

If DH is intentionally centered in a museum, what can, and should, a museum do?

They can be leaders in digital public humanities (and arguably some already are).

1. Digitize Collections

Yep: step 1. There still aren’t enough digital records of collections—particularly for history and natural museums. Publish what you have, warts and all.

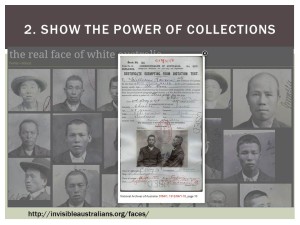

2. Show the Power of Collections once digitized.

Museums have cool stuff—record the traces, histories of them, and share that collections data—and how these represent many voices, histories, unknown individuals, or even species.

We know that these collections are valuable research sources in many contexts. These sources can also make visible, traces and voices of underrepresented people, only look at:

Tim Sherratt’s work with the Invisible Australians project.

Using what was oppressive to expose and identify people who were once made legally invisible. Now, they have faces, and identities visible to us.

3. Be open, adopt an ethos of openness, sharing, and shared responsibility.

This is not only about the collections you have, but about influencing and being the change you aspire to and want to see in the world.

Share knowledge, go where people are, like Wikipedia. One example is this Art and Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon at the Brooklyn Museum. More museums are hosting and participating in these types of events to write into one of the most widely-accessed resources on the web, histories of people of color, women, and other underrepresented groups.

Also, make digital images of your collections open and available, use and encourage others to use fair use.

4. Lead in Digital Public Humanities:

Staff at museums are more likely to be thinking about audiences and community connections. They employ staff whose job it is to communicate to different audiences, with missions to educate, to connect with their communities.

Museums know how to design for specific audiences:

Museums know how to design for specific audiences:

This means being accessible in every way.

Museums understand that design communicates ideas, and understand the value of creating accessible physical and virtual spaces according to different abilities, and making knowledge accessible and welcoming the ideas and questions of those publics.

Establishing a digital public humanities center at a national institution, such as at the Smithsonian, seems to fit with their goals, mission, and history as a research institution.

Establishing a digital public humanities center at a national institution, such as at the Smithsonian, seems to fit with their goals, mission, and history as a research institution.

Museums are generally committed to long-term projects, are institutions in the long game.

Museums are generally committed to long-term projects, are institutions in the long game.

They have physical spaces for centers.

Museums can help push on boundaries of digital humanities, which is still very text based.

Museums can help push on boundaries of digital humanities, which is still very text based.

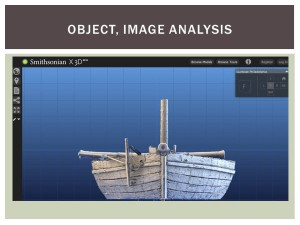

Helping to push on 3D imaging, 3D environments—which are still tricky. SIx3D is a great example; object and image analysis and comparison.

Museums generally employ creative thinkers, designers, and technologists to contribute to these areas of DH. A DH centered in museum might also produce for “DH for Fun†projects.

History museums need the most help. We have to recognize that there are differences in ways that history museum, natural history, anthropology museum, represent objects and contextualize their histories. The stakes can be higher for interpretation.

History museums need the most help. We have to recognize that there are differences in ways that history museum, natural history, anthropology museum, represent objects and contextualize their histories. The stakes can be higher for interpretation.

Art museums, in some ways, have more freedom to play.

Can university museum be a good middle ground for testing out this concept? Is it practical? Or, do DH centers located in university libraries need to reach out to university museums, and vice-versa, to collaborate more.

Establishing a DH Center in a Museum:

Might provide a good place for hosting cross-institutional, trans-disciplinary digital projects.

Provide training for curators and museum staff to learn new skills and implement some new ideas with real projects related to collections and exhibits.

Museums might be the best place to locate digital public humanities centers.