In November 2015, I represented the Omeka team at IMLS’s Focus conference held in New Orleans to share the latest developments in the Omeka software family.

Below are my slides, and the notes from my talk.

I am here representing the Omeka team at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, and we are ever grateful to IMLS who has funded Omeka, from its earliest manifestation in 2007.

I’d like to take you on a brief journey showing you where Omeka started and where we are going related to collections data interoperability and our aspirations for offering GLAMs a way of onboarding to the Linked Open Data landscape.

In the early 00’s, we learned from collaborating with many cultural heritage institutions that there was a need for an easy-to-use, collections-based system that was free and open source, that also adhered to international metadata standards, while also offering organizations the opportunity to build an appealing front-end design that didn’t replicate the look of a database.

We found that we kept building the same type of relational database backend over and over, and decided to generalize it into what is now Omeka.

One of the most important guiding principles, that we are discussing today, is for the data to be portable and accessible in multiple ways.

Data that goes into Omeka, comes out: from the very simple, such as RSS, to more complex formats, including the newest addition, our data API.

Data sharing has always been a core requirement that shapes Omeka’s current development, as the project continues to grow and change.

To increase accessibility of the data, we added an API in Omeka 2.0:

With the API turned on, a user may import all public items and collections, including their files, to be used for other applications

With an API, it’s much easier to push and share content from an Omeka site with other software and applications.

For example, this in-gallery installation at the University of Connecticut Archives is a prototype of the Omeka Everywhere project, an IMLS-funded collaboration with Ideum and the UConn Digital Media and Design Lab. Collections are added into an Omeka site, the Omeka API talks with the API of the Open Exhibits software loaded on a touch table that can publish collections to touch tables for browsing and exploring. This creates continuity between the online and in-gallery experience.

Controlled Vocabularies: The Omeka team has worked to enhance the ease and standardization of metadata input, and over the years, through developing plugins that assist with metadata entry by offering controlled vocabularies, such as the Library of Congress Suggest for LC subject headings and then for all of the LCs authority files.

Our friends at UC Santa Cruz, through their work in the Grateful Dead Archive Online, greatly increased Omeka’s offerings in this area, beyond Library of Congress suggest, to include Getty Research Institute vocabularies to aid in the standardization of metadata entry across individual sites. This standardization, aides greatly when looking outside of one institutions and towards aggregating collections.

We are always grateful for this type of development from the broader Omeka developer community.

With all of this development occurring for Omeka Classic, we are simultaneously building the next generation software package, Omeka S.

Omeka S, which is a new software package designed with medium and larger libraries, archives, and museums in mind.

An outgrowth of lessons learned and feedback from some of Omeka institutional users, Omeka S shares many of the same goals as Omeka Classic (2.x), but none of its code.

Many features of Omeka S will be appealing both to cultural heritage institutions and academic and research libraries, including:

- the ability to administer many sites from a single installation;

- a fully functioning Read/Write REST API, which the system uses to execute most of its own core operations;

- the use of JSON-LD as the native data format, which enmeshes the materials in the LOD universe;

- Native RDF vocabularies that maximize data interoperability, by including Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) Terms; DCMI Type;The Bibliographic Ontology(Bibo); and The Friend of A Friend Vocabulary(FOAF).

- and a set of modules that will aid integration with digital repositories, such as Fedora and DSpace, as well as with one of CHNM’s other major software project’s, Zotero.

- Every Omeka S Resource (item, item set, media) has a URI–unique resource identifier, and will have the ability to embed URIs to connect to existing resources, such as those in DBpedia.

CHNM’s newest NLG grant increases the integration of Linked Open Data authority files in metadata description for digital collections:

- We are building LOD vocabulary modules that will help users create descriptions that capitalize on Linked Open Data through the use of controlled authority files from the Library of Congress and the Getty Research Institute. The use of these standardized description values will increase the discoverability of the digital collections by linking them to the growing semantic web.

- We are also including pathways for institutions to implement their own locally-controlled authorities that allow GLAMs to standardize their descriptions, and contribute to the development of new authorities that might eventually become standards in the field.

To increase the likelihood that newly created metadata for digital collections in Omeka-S can be smoothly transferred to key aggregators within the national digital platform, we are building a resource template that will make Omeka-S data DPLA- ready.

We will offer a basic resource description template based on requirements for the DPLA MAP v.4.0 and the Europeana Data Model, which we hope will help cultural heritage organizations more easily aggregate their data, without requiring messy crosswalks or major data transformations.

Please try Omeka-S!

We are still in the alpha development process, but we are making our newest builds available on GitHub after every 2 sprints, roughly every 4 weeks. This is not something that is quite ready for launching at scale, but we do seek feedback, particularly from our colleagues working in larger libraries and archive.

You may follow our progress, on our blog, in GitHub, or on Twitter (@omeka).

Thank you for your time, and thank you to IMLS for supporting Omeka’s new directions and its place in the national digital platform.

With a nod to my colleague Sharon Leon, this fall, I took an elective! It felt a little indulgent, and I enjoyed the opportunity. I participated in Mason’s Positive Leadership Certificate program which is professional development for both GMU employees and anyone in the greater DC area. I met people doing interesting things at my own institution, as well as others working in government agencies and running small businesses.

This course was steeped in new research from fields in psychology and neurosciences, and focused on how the relatively new specialty of positive psychology can be used to foster workplaces where people thrive. Other topics covered were mindfulness, well-being, coaching, and strengths-based teams and leadership.

Before the program began, I was excited to have the chance to read and think about the building blocks of strong and thriving organizations, but was a little skeptical of what the “positive” meant and nervous this would be too touchy-feely. The course instructors designed exercises that encouraged a lot of self-reflection and discussion, something I wasn’t quite prepared to do with a bunch of strangers. Soon I realized that becoming a good leader or manager begins with you (with me), and the only way to change habits or reactions that our brains do automatically is to be self-reflexive and to practice new habits.

We reflected on our best bosses, and how they made us feel. Often the best bosses were good coaches who asked questioned and listened carefully. It turns out that the list of characteristics of our best bosses matched closely to Gallup surveys & the four themes they summarized that define a good leader:

We reflected on our best bosses, and how they made us feel. Often the best bosses were good coaches who asked questioned and listened carefully. It turns out that the list of characteristics of our best bosses matched closely to Gallup surveys & the four themes they summarized that define a good leader:

- Inviting Trust–competence, respect

- Showing Compassion–empathy, and celebrating and crying together

- Instilling Hope–vision for the future, direction

- Projecting Stability–consistency, security, strength

Instructor Steve Gladdis emphasized that when a leader doesn’t showcase these four qualities, employees can feel like their work isn’t valued, might feel despair because there is no vision for the future of an organization, or they may not want to stay with that organization because it appears to lack stability. Most leaders/managers aren’t born with the ability to do all of these things, most people have to learn and practice to develop these abilities.

Some of the best things I learned related to practicing and cultivating mindfulness. “Mindfulness” as a term is used a lot lately. Our instructor Beth Cabrera relied on Jon Kabat-Zinn‘s definition:”Paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.”

The benefits of mindfulness are a calm, clear mind; focus; and emotional intelligence. Cabrera’s advice to the class was to slow down, stop multi-tasking, go outside, use transitions in our day as cues to STOP–stop, take a deep breath, observe, and then proceed–, and to add meditation into our day. Mindfulness is not something that our brains naturally want to do, so it requires practice.

The benefits are attractive, as it offers individuals more self-control over emotions and increases the ability to handle difficult situations, to truly show compassion, and to help us manage and focus our energies. Big companies are encouraging mindfulness for their employees to help their focus, productivity, and creativity.

Another way for increasing productivity and enthusiasm is for each of us to do things that we are good at and enjoy. We took the Gallup Strengths Finder test, and learned how to balance out teams with people with different skills and strengths. The optimal balance is that 80% of the time we are doing something we are good at and like, leaving 20% for the stuff we do not like. (How does your job stack up?) In class, we discussed being willing as a manager to shuffle tasks and rewrite job descriptions. Often, those small changes often make a big difference in a person’s satisfaction level at work. As does the belief that individuals are contributing on a daily basis to a bigger goal beyond their work stations. Managers and leaders need to remind people about the greater good they are doing.

During class, the historian in me was always thinking about ways that positive psychology and mindfulness practices embraced by large companies today compare with efforts by industrial capitalist to create company towns and factory-based leisure activities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. (Time to do some research.)

Some of the case studies we read about in the class relate more to work environments outside of academia, but still much of it is relevant for anyone who is or wants to become a department chair, an academic advisor, dean, et al. For example, coaching techniques can be useful when advising a student or a peer. Understanding your own strengths and how to put together teams of individuals with complementary strengths and skills is useful in many arenas of academic life. And, mindfulness can not only improve our work, but the kinds of interactions we have with friends, families, and colleagues.

I have been practicing some techniques from the course. I’m trying to start conversations with a question that focuses on the positive: what is going well today? I’m noting things I’m grateful for each day. I’m meditating on my work days, walking outside with my head up and not in my phone to notice the world around me, trying to listen better, and to reduce multi-tasking. The last one is not always easy, since I have prided myself on my efficiency while multi-tasking.

In finding my strengths and learning more about management techniques, I will be thinking how best to use them in my current position and in future endeavors.

Further reading:

The books we read for this course, and a few other resources, are available in this Zotero library.

Natalie Houston often writes in the general area of mindfulness and productivity for ProfHacker.

Harvard Business Review blog offers a lot of interesting articles, many focus on management, but also about organizational structure, social dynamics in the workplace, and other things. If you use the Sage plugin for Firefox, you can read the articles through the feed without needing to subscribe.

As I enter into the final (crossing fingers) revisions of Stamping American Memory, I’ll be trimming and revising. Some sections have to go, because they don’t totally fit. Below is one of them. I’ll save a few sentences for “Who Collected Stamps?” but the rest is gone. So, I’m posting it here for your reading pleasure:

With the emergence of commercial broadcasting in the U.S. in the 1920s, listeners not only tuned in to hear musicians and comedy acts, but also listened to stamp collecting programs. E.B. Powers from Stanley Gibbons’s New York office hosted a program that broadcast on WJY and WJZ in New York, WOR in Newark, and WNAC in Boston. Newspapers listed daily programming from their home city and from other regions that reveal shows running from fifteen minutes to one half hour. Mekeel’s tracked philatelic radio programming and listed nine regular shows in 1932 broadcast from stations in Illinois, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey. By 1936, more than 60 stations broadcasted philatelic shows. Those who listened regularly were exposed to stamp collecting practices and “the drama of the postage stamp.†[note]I have not been able to locate any transcripts or recordings of these stamp programs. Powers’s programs were broadcast in different stations and markets. It is possible that the programs began because radio stations needed to fill air time and daytime programming lacked competition in the early days of broadcasting. “Today’s Radio Program,†New York Times, January 15, 1924, 21; “Today’s Radio Program,†New York Times, February 5, 1924, 17; “Today’s Radio Programs,†Chicago Daily Tribune, January 3, 1924, 6; “Radio Programs,†Washington Post, March 25, 1924, 16; “Broadcasts Booked for Latter Half of the Week,†New York Times, August 12, 1928, sec. XX, 16.; “Chicago Radio Talks,†Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 46, no. 39 (September 26, 1932): 476; “Radio Philately,†Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 46, no. 41 (October 10, 1932): 504.; and Frank L Wilson, The Philatelic Almanac: The Stamp Collector’s Handbook (New York: H.L. Lindquist, 1936), 110–11. For a few sources on the history of commercial radio, see Alice Goldfarb Marquis, “Written on the Wind: The Impact of Radio During the 1930s,†Journal of Contemporary History 19, no. 3 (July 1984): 385–415; Susan Smulyan, Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994); Susan J. Douglas, Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899-1922, Johns Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987).[/note]

As radio emerged as a medium to advertise as well as to provide entertainment and news, it is not surprising that professional stamp dealers like Powers hosted the program and served as the philatelic expert. His presence on American radio not only spread the word about philately, but may have also encouraged the commercial side of collecting and investing. It is unclear whether Gibbons officially sponsored these programs, but it is easy to see how Powers could promote his company as the place to shop or consult for philatelic advice.

Radio not only broadcasted stamp collecting programming, but it also connected collectors and helped them obtain new specimens. When listening to KDKA in Pittsburgh, one collector learned that the station received a letter from the United States Shipping Board vessel Cathlamet, detailing that the ship picked up the station’s signal on the radio while sailing near what is now Ghana on the west coast of Africa. While the station was thrilled that their wireless waves carried that far, the collector contacted the station and asked for the envelope bearing the letter read on air. To his delight, the director saved the envelope and the collector went to the station to pick up the envelope affixed with a stamp from the Gold Coast British colony (now the nation of Ghana). According to this individual, “stamp collecting and radio were working in harmony at last!†First published in the New York Times, this story was reprinted for philatelic audiences in the Philatelic West. [note]“Stamp Collector Finds Radio Useful in Locating Specimens,†New York Times, January 23, 1927, sec. X; and “Stamp Collector Finds Radio Useful in Locating Specimens,†Philatelic West 85, no. 3 (May 1927): n.p.[/note]

Other collectors combined an interest in short-waved radio with philately. Part of the thrill for George Mathewson and other amateur radio enthusiasts was communicating with hobbyists in other countries. To create a written record of such communication, each operator sent a letter or postcard from their hometown and country that the other would sign and postmark. For Mathewson, the act of receiving many foreign-stamped letters turned him into a stamp collector. Once he established contacts in other nations, he then actively requested stamps from those with whom he communicated. Additionally, as radio listeners tuned into as many stations across the country as possible, they then mailed out postcards to those stations who returned the cards with a unique (non-postage) stamp verifying contact. Radio hobbyists collected those cards and pasted them, with unique station stamps, into albums produced for this purpose, creating a type of “radio philately.†[note]Kristen Haring, Ham Radio’s Technical Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007); “Stamp Collector Finds Radio Useful in Locating Specimens,†New York Times, January 23, 1927, sec. X, 16; “Stamp Collector Finds Radio Useful in Locating Specimens,†Philatelic West 85, no. 3 (May 1927): np; “Amateurs Becoming Radio Philatelists,†Christian Science Monitor, November 4, 1924, 6; George M. Mathewson, “Radio Philately,†Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 43, no. 41 (October 14, 1929): 616.[/note] Stamp collecting meshed well with radio enthusiasts’ interest in seeing how far their signals traveled and in connecting with others with similar interests.

As philatelic information spread in different media, stamp collecting attracted new practitioners and appealed to the interests of different people. Magazines, newspapers, and radio programs brought some activities that had been exclusive to philatelic clubs and publications out into a public realm. For collectors who did not belong to a club, this exposure increased their philatelic knowledge or allowed them to connect with the philatelic community through the media. This media presence also exposed non-collectors to the hobby and taught them that many people saw something special in stamps and spent time collecting them.

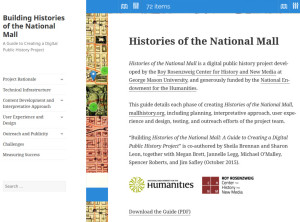

I am really pleased that the @mallhistory team published Building Histories of the National Mall: A Guide to Creating a Digital Public History Project (http://mallhistory.org/Guide) this week. It is a comprehensive guide that details each phase of creating website, Histories of the National Mall. This is also the final deliverable for a project that was five years in the making.

I am really pleased that the @mallhistory team published Building Histories of the National Mall: A Guide to Creating a Digital Public History Project (http://mallhistory.org/Guide) this week. It is a comprehensive guide that details each phase of creating website, Histories of the National Mall. This is also the final deliverable for a project that was five years in the making.

One nice feature is that the voices of project team members are heard in specific sections they authored, that also demonstrate the range and breadth of the collaboration and cooperation that produced mallhistory.org.

For organizations in the early planning stages of a project, this guide offers an open source and replicable example for history and cultural heritage professionals wanting a cost-effective solution for developing and delivering mobile content. The guide offers lessons learned and challenges we faced throughout the project’s development, and we discuss how we measured success for this specific project.

This guide goes beyond a traditional case study and is divided into seven main sections, including the project’s rationale; content development and interpretative approach; user experience and design; outreach and publicity–including the social media strategy. This publication shares the project team’s decision to build for the mobile web and not a single-use, platform-specific native app. The guide also offers lessons learned and challenges faced throughout the project’s development, as well as how the team measured success for this digital public history project.

One aspect that most readers might not realize is that Histories of the National Mall grew out of R&D conducted by my colleague Sharon Leon and I in 2009, funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, Mobile for Museums. I have remained connected to mobile-driven content within the cultural heritage sector and for place-based public history projects.

Building Histories of the National Mall belongs to the long tradition of knowledge sharing at RRCHNM that encourages history and humanities professionals to be active designers and builders of their own digital projects, and for making processes as transparent as possible.

Home in New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward

(Originally posted on the RRCHNM blog, August 28, 2015)

Ten years ago, we knew as historians that we couldn’t assess fully the social, cultural, economic, and political implications of the devastating hurricanes in the summer of 2005. We did know that previous natural disasters had profound consequences. The 1927 Mississippi River Flood, for example, further fueled African American migration to northern industrial cities, and paved the way for federal intervention in southern states during the New Deal. Documenting the reactions and memories of individuals affected by Katrina, and then Rita, along the Gulf Coast, took on an urgency soon after the storms hit.

Michael Mizell-Nelson, the late-public historian from the University of New Orleans, reached out to CHNM’s late-director Roy Rosenzweig to discuss the possibilities of creating a community-sourced digital project to document the aftermath and recovery of Hurricane Katrina. With so many residents relocating, collecting online gave anyone who had been displaced an opportunity to share their reflections and document their stories. This became even more important following Hurricane Rita three weeks later, when some Gulf Coast residents evacuated a second time, some never returning home.

The Center collaborated with the University of New Orleans to form a team that built read more…

Tomorrow is the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, and I wrote a post for the RRCHNM blog post discussing the history and legacies of the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank, which I helped to create.

One advantage to collecting online first, is that we have thousands of sources available for close reading that are discoverable by browsing or key word searches. My colleague Mills Kelly has highlighted some of those individual stories on his blog today.

HDMD also provides content ready for computational analysis, and research can be done at scale. I hadn’t had the time to do any myself, until this week.I started with the HDMB databases in PHP MyAdmin and downloaded a few tables as CSV files.

At first, I wanted to some basic calculations and summaries of the contributors to include in the About section of the project. For researchers, it is important to know whose voices are speaking and represented. As a project creator, I wanted to see where we succeeded and failed in outreach efforts. We asked each online contributor a few optional demographic questions so that we could better track who was sharing stories, photos, and other digital materials with us. What I found is that few contributors shared any of that demographic information with us (gender, race, year of birth, occupation). We also asked for contributors to share the location or zip code of where they were during the storms, and then after the storms, to get a broader sense of the migrations. All of these questions were optional, intentionally.

The project team debated these issues intensively. As historians, we wanted to collect some general demographic information about the contributors. We also did not want a long list of required questions in an online form to discourage someone from submitting a story. Balancing out those needs was tough and we decided that collecting the reflection or the photograph was a priority.

The next table I examined contained the full list of all items, and I extracted the descriptions. In the second iteration of the site, completed in 2006, we mapped text from “stories”, and image and other file descriptions to the Dublin Core description field.

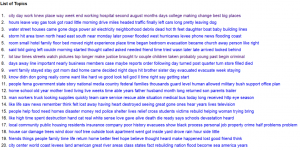

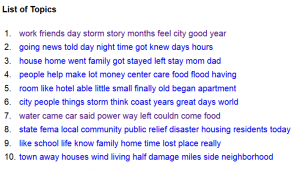

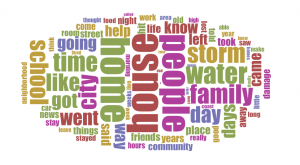

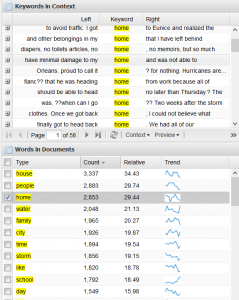

I uploaded that CSV into the Voyant Tools to surface word patterns and trends across the 25,000 + digital items. In addition the ubiquitous word cloud, I could also see word frequencies and view relationships of terms in context with others.

Not surprisingly, place names featured prominently in individual contributions. To look beyond the names of cities, parishes, or states, it is possible to create a list of “stop words†that removes those terms from the analysis. Without place names, it is possible to see that HDMB’s contributors frequently mentioned “people,†“home,†“house,†and “family.†By examining those keywords in context, it is possible to see how mentions of “house†relate to the descriptions of physical damage and destruction. While usages of “home†often discuss the emotions of leaving or returning to a damaged house or city. It is possible to identify other emotional terms, such as “loss†and “angry,†and see that “hope†is invoked as a verb and a noun more often than both loss and angry.

Not surprisingly, place names featured prominently in individual contributions. To look beyond the names of cities, parishes, or states, it is possible to create a list of “stop words†that removes those terms from the analysis. Without place names, it is possible to see that HDMB’s contributors frequently mentioned “people,†“home,†“house,†and “family.†By examining those keywords in context, it is possible to see how mentions of “house†relate to the descriptions of physical damage and destruction. While usages of “home†often discuss the emotions of leaving or returning to a damaged house or city. It is possible to identify other emotional terms, such as “loss†and “angry,†and see that “hope†is invoked as a verb and a noun more often than both loss and angry.

In thinking through what other patterns might become visible, I decided to run that corpus through a light-weight topic modeling tool.

At first, I ran all item descriptions and asked for 20 words for 20 topics.

As I ran the text, I continued to refine the stop word list. I noticed that contractions were split, so that “don”, “ll”, and “ve” were coming through.

Once I created a good stop word list, I decided to run a CSV with the Story item type only, and reduced the numbers of topics and terms per topic.

I was able to get a good hint at who some of the contributors were, as the terms students and school featured prominently in the stories. Students, teachers, and/or parents discussed how the storms effected their school years.

It is possible to see that this digital collection would be useful for someone interested in reading first-hand accounts about evacuations; life in temporary housing, such as in shelters or hotels; relief efforts; the challenges of returning home to deal with damages;Â the emotional challenges faced in the recovery process and the roles of families; the financial burdens faced by storm survivors; and the impact of local, state, and federal government in a disaster.

With these topic strings identified, I then drilled down and read individual text. In the earliest years of the project, I read many of the contributions but 10 year later, had forgotten so much of what I had read.

This exercise allowed me to rediscover some of the resources in the site. I also did a lot of old-fashioned browsing through the collections of photographs.

As I turned up topics, I really wanted to discuss these trends with Michael and Roy, both whom are now gone. I found that researching in HDMB was surprisingly emotional for me. I can imagine that this anniversary has been difficult for the millions of people who were intimately effected, and who are still feeling personal losses of varying degrees ten years later.