DH Centered in Museums?

On Thursday, March 12, 2015, I had the pleasure of speaking at John Nicholas Brown Public Humanities Center with students, faculty, and staff at Brown University. Professor Susan Smulyan also invited me to speak in one of her graduate courses earlier in the day about planning digital public humanities projects. Her students are planning some really neat digital projects. I enjoyed the short time I spent in Providence.

During my talk, took the opportunity to discuss other futures of digital humanities outside of the university.

Here are my slides, and below are my notes per slide. Since the talk was conversational, below are my notes which may not reflect the exact words spoken.

In November, RRCHNM celebrated its 20th anniversary, marking it as the oldest digital history center, and one of the oldest digital humanities centers in the world. Of those speaking, three of the four direct digital humanities centers at universities. The other oversees the Office of Digital Humanities at the NEH and has been tracking the development and recent expansion (explosion) of DH centers on college campuses.

As I sat and listened, I was surprised to hear that no one really talked about the future of centers as existing outside of the university. In fact, some of the futurist possibilities of centers in academic libraries that might allow for speculative computing or play (Nowviskie), are really only possible at well-funded universities—-mine not being one of them. But, I could see that type of process play happening at a museum.

Some of what I did hear resonated: DH Centers benefit from the diversity of skills the concentrate (Ayers); DH Centers are good places for organizing and implementing large-scale projects that cut across disciplines and institutions (Bobley); the academic institutions where centers reside need to commit funding to their long-term stability (Bobley). These seem congruous to how larger museums are staffed, how they collaborate, and how they keep their doors open.

These discussions focused on DH centers in universities, and there are many DH Centers in libraries on college campuses. But, none, as far I know of, in university museums.

No one imagined DH—as a constructed field of practice–centered elsewhere.

What if there were DH centers in museums?

I thought I would take this opportunity to think about the possibilities of DH centers outside of academia. And I’d like to discuss with you all, if this makes sense, if it is practical, or if we all just need to collaborate more.

First, let’s look at DH that is already happening in museums:

I agree with my friend Kimon Keradmidas at the Bard Graduate Center who asserts that DH happens in museums, but just isn’t called that.

“Digital humanities†as I’ve been reminded for years by my colleagues in the museum technology community is a very academic term, and is irrelevant to some, even as it may provide new inroads to scholarly production, discovery of resources, and questions, and opening up some of this work to audiences outside of the academy.

Museums don’t need to get bogged down in definitions that are limiting. Thinking broadly helps to think of multiple roots to DH and to its multiple futures.

I’m not the only one who has been thinking about these communities and bridging and working in ways that enables commons of shared digital resources that benefit many, and driven by museums and dedicated staff.

Neal Stimler of the Met, Mike Edson of the Smithsonian, Mia Ridge of Open University, to name a few. In 2011, Neal Stimler put together a virtual panel of individuals talking about DH in Museums. And there was another panel hosted by CUNY on the Commons, DH in Museums, in Nov 2012.

Mike’s call that museums matter NOW, and that they matter to many publics including scholars, enthusiasts, and visitors of all ages, as museums nurture creativity, civic engagement, knowledge creation. And can do those jobs in better and new ways through digital platforms and methods.

The Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum is one of the best examples of letting Digital Strategies shape their interpretative strategies who also have an amazing lab in the heart of it all.

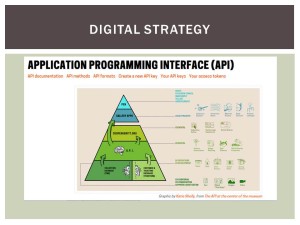

Cooper-Hewitt is running on an API that drives development of in-person, distance visits, and enables their collection to connect with other digital cultural resources.

When there is an API, with collections data, others can do things with it.

And there is the pen.

Enables physical interaction while at the museum—actual drawing on touch tables. You touch labels, click and save objects from your visit to your own personalized collection page to look at later.

Once collections are available via an API, others can use them and put them into context with other objects:

Rich Barrett-Smith of the Victoria and Albert Museum built Colour Lens—visualizing collection by colors

Makes use of featuring Public Domain images from the Rijksmuseum and the Walters Art Museum, others with permission from the Wolfsonian-FIU, and code from Tate and the Cooper-Hewitt.

Experiments with that data is then shared, on places for sharing open source code, like GitHub.

New modes of Digital publishing, like the Getty Foundation sponsored OSCI Tool Kit, Online Scholarly Catalog Initiative, at art museums.

Scholarly editions, translations of artist works, such as the Van Gogh Letters, Van Gogh Museum was a major partner. Idea to create a new edition, international appeal.

What have you noticed about all of these projects so far?

Art museums

DH Scholars are working with museums, too, such as Ben Schmidt of Northeastern with the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and visualizing 100 years of shipping routes, commodities routes.

Sharing Authority: again the Cooper-Hewitt is asking for input—help us make our data better—not only scholars, but others who might be enthusiasts in a field of expertise.

Curators of American Enterprise exhibit were reaching out, asking for stories that might influence the interpretation and make it into exhibition.

Move toward Openness: Open GLAM, open-source, public domain.

Making museum-quality images available for public uses.

Linked Open Data—connecting collections, persons, places, across institutional repositories.

Example: Smithsonian American Art Museum is leading a group of fourteen institutions from around the country in an effort to build a shared—and searchable—online database of American art, available through Linked Open Data.

Growing number of Maker Spaces in Museums.

That encourage learning, teaching, and tinkering with different varieties of technologies, from sewing to arduinos. Peabody-Essex has a Maker Lounge, and a Maker Lounge Resident focusing on industrial design.

Los Angeles Contemporary Museum of Art has one focusing on art and technology.

It’s a physical space, not unlike some museum education-focused spaces, or maker spaces in libraries. You don’t need a 3D printer to be a maker space.

If DH is intentionally centered in a museum, what can, and should, a museum do?

They can be leaders in digital public humanities (and arguably some already are).

1. Digitize Collections

Yep: step 1. There still aren’t enough digital records of collections—particularly for history and natural museums. Publish what you have, warts and all.

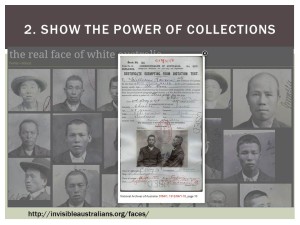

2. Show the Power of Collections once digitized.

Museums have cool stuff—record the traces, histories of them, and share that collections data—and how these represent many voices, histories, unknown individuals, or even species.

We know that these collections are valuable research sources in many contexts. These sources can also make visible, traces and voices of underrepresented people, only look at:

Tim Sherratt’s work with the Invisible Australians project.

Using what was oppressive to expose and identify people who were once made legally invisible. Now, they have faces, and identities visible to us.

3. Be open, adopt an ethos of openness, sharing, and shared responsibility.

This is not only about the collections you have, but about influencing and being the change you aspire to and want to see in the world.

Share knowledge, go where people are, like Wikipedia. One example is this Art and Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon at the Brooklyn Museum. More museums are hosting and participating in these types of events to write into one of the most widely-accessed resources on the web, histories of people of color, women, and other underrepresented groups.

Also, make digital images of your collections open and available, use and encourage others to use fair use.

4. Lead in Digital Public Humanities:

Staff at museums are more likely to be thinking about audiences and community connections. They employ staff whose job it is to communicate to different audiences, with missions to educate, to connect with their communities.

Museums know how to design for specific audiences:

Museums know how to design for specific audiences:

This means being accessible in every way.

Museums understand that design communicates ideas, and understand the value of creating accessible physical and virtual spaces according to different abilities, and making knowledge accessible and welcoming the ideas and questions of those publics.

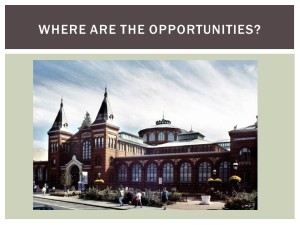

Establishing a digital public humanities center at a national institution, such as at the Smithsonian, seems to fit with their goals, mission, and history as a research institution.

Establishing a digital public humanities center at a national institution, such as at the Smithsonian, seems to fit with their goals, mission, and history as a research institution.

Museums are generally committed to long-term projects, are institutions in the long game.

Museums are generally committed to long-term projects, are institutions in the long game.

They have physical spaces for centers.

Museums can help push on boundaries of digital humanities, which is still very text based.

Museums can help push on boundaries of digital humanities, which is still very text based.

Helping to push on 3D imaging, 3D environments—which are still tricky. SIx3D is a great example; object and image analysis and comparison.

Museums generally employ creative thinkers, designers, and technologists to contribute to these areas of DH. A DH centered in museum might also produce for “DH for Fun†projects.

History museums need the most help. We have to recognize that there are differences in ways that history museum, natural history, anthropology museum, represent objects and contextualize their histories. The stakes can be higher for interpretation.

History museums need the most help. We have to recognize that there are differences in ways that history museum, natural history, anthropology museum, represent objects and contextualize their histories. The stakes can be higher for interpretation.

Art museums, in some ways, have more freedom to play.

Can university museum be a good middle ground for testing out this concept? Is it practical? Or, do DH centers located in university libraries need to reach out to university museums, and vice-versa, to collaborate more.

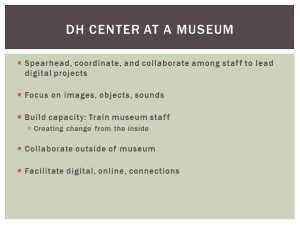

Establishing a DH Center in a Museum:

Might provide a good place for hosting cross-institutional, trans-disciplinary digital projects.

Provide training for curators and museum staff to learn new skills and implement some new ideas with real projects related to collections and exhibits.

Museums might be the best place to locate digital public humanities centers.