Letting the Collections Out, Letting the Ephemeral In

At this year’s National Council of Public History conference, I organized a panel on ephemerality in public History with Mark Tebeau of Arizona State University and Director of CurateScape, and Yolanda Chávez Leyva of University of Texas El Paso, and Director of el Museo Urbano.

We talked about ways to embrace the ephemeral in our work, as we engaged in discussion about sustainability (the conference theme) by challenging our ideas of permanence and preservation. We each argued that ephemerality and performance are vital to the future of history museums and public history practice. In light of discussions about sustaining digital assets, we reconsidered the physical, asking are stuck on the notion that we must save things forever?

You can just view my slides here:

Or, read the notes from my talk with each slide.

Ephemeral experiences abound to public history.

My colleagues are addressing some of these experiences.

My colleagues are addressing some of these experiences.

Even in the digital world, where we leave many traces in our social networks and online profiles, there are attempts to create “ephemeral†experiences—online happenings, Chats, real-time conversations, hangouts, and apps that facilitate those experiences such as SnapChat.

The founder of SnapChat, Evan Spiegel, spoke of the appeal and distinctiveness of the SnapChat program—which lets you send a text or photo that disappears from your phone after so many seconds. He attributes the ephemeral qualities to this new category of online experiences as attractive ones: “The embrace of the Ephemeralnet comes in stark contrast to the previous generation of social networks, in which what people shared was forever tied to their online identities. Those communications are happening anonymously, or they happen in real time and disappear.”

The founder of SnapChat, Evan Spiegel, spoke of the appeal and distinctiveness of the SnapChat program—which lets you send a text or photo that disappears from your phone after so many seconds. He attributes the ephemeral qualities to this new category of online experiences as attractive ones: “The embrace of the Ephemeralnet comes in stark contrast to the previous generation of social networks, in which what people shared was forever tied to their online identities. Those communications are happening anonymously, or they happen in real time and disappear.”

A few years ago, my colleague Mark Sample asked “What about the fine act of disappearance?” He discussed the somewhat radical idea of not trying to save everything that we create in a digital age, merely because we can: “We record the metadata but not the data. We celebrate the trace, and bid farewell to texts that by accident or design fade, decay, or simply cease to be… Let the archive be loved. But fugitive texts will become legend.”

What if we thought about ephemerality and traces in terms of collections?

In considering the conference theme of sustainability, I want to discuss the topic of sustaining collections by using the ones we have to make room for new ones and challenge current practice that demands perpetuity of physical cultural heritage.

I’ve returned to Susan Crane’s piece on “The Conundrum of Ephemerality: Time, Memory, and Museums” to think about the problem of “fixed ephemerality†in museums. She discusses the ways that museums collect objects that are frozen in time and then “denied their natural…lifespan.†Objects never designed to last a long time do. We “preserve, protect, defend the objects we choose to represent our past & our cultures†because they are of value to us. “The narratives, however, will change, and that too is a part of the natural history of preservation and destruction.â€

History institutions collect for specific reasons, or they maintain collections given them based on someone’s desires, tastes, and interests, and the willingness of a curator at some time to accept them.

Objects are saved and conserved.  Lots of money and space is required to carefully care for collection objects. For many objects in history museum their life in a museum is the best life they’ve had. Temperature control, custom boxes, handling with gloves and care, and almost no one sees or touches them. The lifecycle of those objects have been slowed, as it preserved.

Lots of money and space is required to carefully care for collection objects. For many objects in history museum their life in a museum is the best life they’ve had. Temperature control, custom boxes, handling with gloves and care, and almost no one sees or touches them. The lifecycle of those objects have been slowed, as it preserved.

The object might be cared for but is it used?

So often when we discuss digital collections/replicas or photographic representations of physical objects, we often say that the original still holds a transformative power that can only occur in person–an ephemeral, but lasting experiences. I believe in that.

Yet, rarely does anyone outside of museum staff get to interact or experience these collection objects.

Here is a rare peek inside of a dollhouse on display at the National Museum of American History Museum for some lucky visitors:  These visitors were thrilled to catch a glimpse inside the dollhouse, which is a popular item, that was out of its case to be decorated for the holidays.

These visitors were thrilled to catch a glimpse inside the dollhouse, which is a popular item, that was out of its case to be decorated for the holidays.

We know from Steven Conn’s research that less exhibition space is available for objects in many museums, and exhibitions are relying on fewer objects to carry the interpretative burden. Meanwhile, more objects are taking up storage space than working as material culture evidence in a museum. Is conserving objects forever sustainable?

How can history museums of all sizes expand their collections to include collections of today’s world? How can we make room for the objects and stories around us now that haven’t been collected and saved?

How many new museums will be needed to interpret the late 20th and early 21st centuries, or can our existing institutions open up to handle new histories?

There will be new museums, because of the demands of communities, like the Red Location Museum in one of the oldest-settled black townships, Port Elizabeth, Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa. Port Elizabeth was a major site of resistance to Apartheid in South Africa. It demands from its participants that they be active, and there isn’t one narrative told. This museum was demanded from its residents to tell their stories because no state-funded institutions were doing that.

There will be new museums, because of the demands of communities, like the Red Location Museum in one of the oldest-settled black townships, Port Elizabeth, Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa. Port Elizabeth was a major site of resistance to Apartheid in South Africa. It demands from its participants that they be active, and there isn’t one narrative told. This museum was demanded from its residents to tell their stories because no state-funded institutions were doing that.

Can some of our regional and local historical institutions adapt and make room in their collections for today’s history, and for the uncomfortable stories of their recent past?

In talking with other historians, curators, and state humanities council reps, there is a growing problem, that has not been systematically documented, indicating that the mid-sized and small historical societies, serving local and regional communities, are not collecting. They do not have the space, and are concerned about how to maintain what they currently have. This is understandable, but troubling. How can we create people’s history without the objects from people in our community?

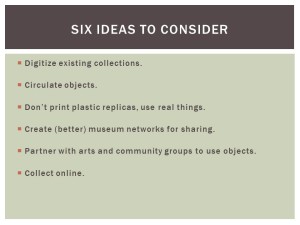

I propose a few crazy ideas for us to think on in the name of sustainability of collections, and also our history institutions, and the ability to interpret the history of our lives today, tomorrow.

- Digitize what we have; record its uses, record it in action.

Take collections records, warts and all, and make that metadata and a digital replica accessible on the open web. Take a quick video. Save, upload. This cultural heritage is mostly invisible now, it needs to be visible.

Take collections records, warts and all, and make that metadata and a digital replica accessible on the open web. Take a quick video. Save, upload. This cultural heritage is mostly invisible now, it needs to be visible. - Take objects out of storage, or out of cases and let them degrade gracefully. De-accession when possible.

I’m not asking for everything to be spilled out:

I’m not asking for everything to be spilled out:

But, how many chairs can be stored and what is the history it is telling? Allow visitors to truly interact with the things that drew them inside the museum in the first place.

We all talk about the power of objects, but rarely are we allowed to directly engage with them at a museum. In my former museum, visitors remarked to me regularly how much they enjoyed that many of the objects were out, touchable. That was our value, distinguished us from other museums. In-person experiences, with context, help teach about specific experiences. Think about the teaching collections that can come with de-accessioning more objects.

For instance Robert E. Lee’s chair—and accompanying lesson plan:

Can students sit in the chair? Or is this still an observational skill? Sit in the chair. There is an opportunity to create more tactile experiences available to visitors using the real thing.

Can students sit in the chair? Or is this still an observational skill? Sit in the chair. There is an opportunity to create more tactile experiences available to visitors using the real thing. - Don’t pay for artifakes or make replicas with 3D printers.

Museums regularly pay for replicas for exhibitions and for teaching collections. Why not use the real thing, and let it wear down from human use?

Museums regularly pay for replicas for exhibitions and for teaching collections. Why not use the real thing, and let it wear down from human use?

The Maker Movement is really hot now, and libraries and museums are encouraging creativity and building with active learning spaces. Visitors of all ages are developing skills such as knitting, circuitry, and technical skills. Often, there are 3D printers involves. I’m watching this carefully, and I like that this movement returns the physical in a very digitized and digital world. But one thing that troubles me about 3D printing is that the process creates more plastic stuff. I’m not saying there isn’t value in the design and in learning some technical skills, but we don’t need 3D printers to make the museum touchable. This is an advantage history museums have over art museums, so let’s take that advantage.

There is tremendous popular interest in objects in many televisions show on Discovery and History Networks. The problem is that everyone on these shows is looking to make money from their collections. This is the real consumer capitalist side of collecting, and one that museum curators will not be involved in –such as offering appraisals, et al.

There is tremendous popular interest in objects in many televisions show on Discovery and History Networks. The problem is that everyone on these shows is looking to make money from their collections. This is the real consumer capitalist side of collecting, and one that museum curators will not be involved in –such as offering appraisals, et al.What is fascinating to me about these shows is that everyone has objects in their homes, barns, closets, attics. And most of the individuals are fascinated and connected at some level with these objects. They are stirring interest in audiences. All of these objects can be touched, felt, examined closely. Why not showcase a few more objects inside a museum with the bonus of offering expertise from curators and educators.

- Create regional coalitions to share collections and consolidate topically.

Are there ways to share these collections, for public handling, among regional coalitions to help fill in gaps in collection areas, to make room for new ones? To think less individually and consider our cultural heritage in a more collective way–contributing to a cultural commons. There was an effort to do this type of collaborating in the late 1980s, early 1990s, that never caught on. (Thanks to Jim Gardner for this reminder.) Let’s return to this idea.

Are there ways to share these collections, for public handling, among regional coalitions to help fill in gaps in collection areas, to make room for new ones? To think less individually and consider our cultural heritage in a more collective way–contributing to a cultural commons. There was an effort to do this type of collaborating in the late 1980s, early 1990s, that never caught on. (Thanks to Jim Gardner for this reminder.) Let’s return to this idea. - Partner with other arts organizations to use our collections and to share them:

Imagine if a history museum and a theater company partnered on a project like the musical Sleep No More and used collections from a museum in their sets?

Imagine if a history museum and a theater company partnered on a project like the musical Sleep No More and used collections from a museum in their sets?

The set for this retelling of Macbeth is a series of rooms in the multi-story McKittrick Hotel. Objects for the set were acquired from antique stores, junk dealers, flea markets. Everything was touchable, interactive as you wished. I loved this. The entire experience of Sleep No More is different each time, because the actors interact with the audiences and sometimes improvise the scenes. How could a museum enrich that experience?

I recently read a fantastic example on the History@Work blog about a pop-up museum from the St. Catharines Museum in Ontario Canada. They used spaces outside of a museum to engage visitors, and to bring artifacts into the world.

The museum staff’s favorite response to this event was “aMUSE is so great because not only can you interact with the artifacts in a space away from the ‘traditional, stuffy museum’ but on top of that, you can drink a beer, hang out with friends and listen to great music with history all around you.â€

And the response from the museum: “The staff and volunteers here at the museum were all in agreement about the need for this type of outreach, even with the logistical nightmare that moving artifacts outside of a controlled museum space presented.†(I love this, and also say—use an artifact.)

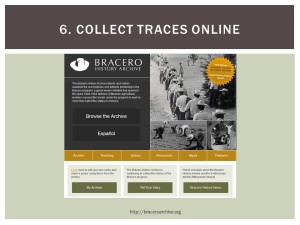

- Collect traces online.

When there is no place, make a place, and collect what you can online.

When there is no place, make a place, and collect what you can online.

Projects like the Bracero History Archive and History Harvests scheduled community scanning and collecting days. Students, librarians, curators work together to digitize personal objects not in museums, but that come from people’s homes.

Objects are photographed, paper is scanned, and items are immediately made them available online. All items brought to the community scanning and harvest days are then given back.

In our efforts in this panel to re-consider the physical in the digital age, I have focused on collections in the name of staying relevant, and sustaining museum collections and the institutions themselves.In conclusion I want to use the words from Nick Poole, the Director of the Collections Trust in the UK and brainchild of Europeana—the aggregated collections service for cultural heritage metadata from European collecting institutions. He offered up these suggestions in his keynote at the WebWise 2014 Conference in February.

He remarked that cultural heritage institutions should be in their heyday, but they face 2 big challenges: relevance and value.

the reality for many of us is that our institutions have stopped moving forward, and quietly the job has become to protect and document perfectly a specific body of material acquired between 1890 and 1980… This should be our heyday – the age demands exactly what we have – authenticity, expertise in filtering and connecting, giving people the skills to curate their own digital lives. But when people come to us for experiences that are immediate and personal and relevant, all too often what they get is an undifferentiated shopping list of everything we’re keeping in our store-rooms.

In this connected age, we have to find a way of learning that value is what flows through us, not into us.

Let’s not let our collections be fixed in time, or fixed on representing only the lives or whims of elite collectors. We don’t want or expect collections to disappear as quickly as a Snapchat conversation. But, I think we can imagine using collection objects–the authentic objects–to help create meaning and generate conversations with different public audiences.

And once we let some of these objects decay, we can also make some physical space for the histories of the communities our museums serve today.

Let them go!